Bouquet Expedition of 1763

Colonel Henry Bouquet led an expedition into the Ohio country to put down an Indian uprising that later came to be called Pontiac’s Rebellion.

So why is this Expedition so important? One of our Adams ancestors fought in this battle. His name was Robert Adams (1745-1776), Son of Thomas and Katherine Adams of Toyborne Township, Pennsylvania.

In 1763, Pontiac, a leader of the Ottawa Indians, successfully united many of the tribes in the Ohio Country. His goal was to drive English settlers, traders, and soldiers from the Ohio Country. Pontiac’s Rebellion, as it became known, was a direct result of the French and Indian War. In 1763, after England’s victory in the war, the British government acquired all of France’s colonies in North America. This created fear among the Ohio natives, due to the large and increasing number of English colonists in North America. While the French were in North America, the Indians could count on them for military assistance against the English as well as a steady supply of guns and ammunition thanks to the fur trade. With the French gone from North America, the natives’ situation had become precarious at best.

The first year of Pontiac’s Rebellion went badly for the English. The Native Americans drove most English people from the Ohio Country. England’s two most important fortresses west of the Appalachian Mountains, Fort Detroit and Fort Pitt, nearly fell. The Indians successfully captured Fort Sandusky and murdered the entire garrison. Hundreds of other English colonists either died or were captured.

In 1763, Pontiac’s War began on the frontier. Pontiac, an Ottawa war leader, urged the defeated Indian tribes that had been allied to the French during the to join unite and continue the fight against the British. Pontiac initiated attacks on frontier forts and settlements, believing the defeated French would rally and come to their aid. The conflict began with the siege of Fort Detroit on May 10, 1763. Fort Sandusky, Fort Michilimackinac, Fort Presque Isle, and numerous other frontier outposts were quickly overrun.

Several frontier forts in the Ohio Country had fallen to the allied tribes, and Fort Pitt, Fort Ligionier, and Fort Bedford along Forbes’s road were besieged or threatened. Bouquet, who was in Philadelphia, threw together a hastily organised force of 500 men, mostly Scots Highlanders, to relieve the forts. On August 5, 1763, Bouquet and the relief column were attacked by warriors from the Delaware, Mingo, Shawnee, and Wyandot tribes near a small outpost called Bushy Run, in what is now Westmoreland County, Pennsylvania. In a two day battle, Bouquet defeated the tribes and Fort Pitt was relieved. The battle marked a turning point in the war.

It was during Pontiac’s War that Bouquet gained a certain infamy. In a series of letters during the summer of 1763 between Bouquet and his commander, General Jeffery Amherst, the idea was raised of infecting the Indians who had besieged Fort Pitt with smallpox by giving them infected blankets from the fort’s smallpox hospital. Amherst wrote to Bouquet, then in Lancaster, on about June 29, 1763: “Could it not be contrived to send the small pox among those disaffected tribes of Indians? We must on this occasion use every stratagem in our power to reduce them.”[1] Bouquet agreed, replying to Amherst on July 13: “I will try to inoculate the Indians by means of blankets that may fall in their hands, taking care however not to get the disease myself.”[2] Amherst responded on July 16: “You will do well to try to inoculate the Indians by means of blankets, as well as to try every other method that can serve to extirpate this execrable race.”[3]

Evidence that at least some measure of this plan was carried out is provided by the journal of William Trent, commander of the militia at the fort, though it appears that Trent had already done this before Amherst had proposed it to Bouquet:

[June] 24th [1763] The Turtles Heart a principal Warrior of the Delawares and Mamaltee a Chief came within a small distance of the Fort Mr. McKee went out to them and they made a Speech letting us know that all our [POSTS] as Ligonier was destroyed, that great numbers of Indians [were coming and] that out of regard to us, they had prevailed on 6 Nations [not to] attack us but give us time to go down the Country and they desired we would set of immediately. The Commanding Officer thanked them, let them know that we had everything we wanted, that we could defend it against all the Indians in the Woods, that we had three large Armys marching to Chastise those Indians that had struck us, told them to take care of their Women and Children, but not to tell any other Natives, they said they would go and speak to their Chiefs and come and tell us what they said, they returned and said they would hold fast of the Chain of friendship. Out of our regard to them we gave them two Blankets and an Handkerchief out of the Small Pox Hospital. I hope it will have the desired effect. They then told us that Ligonier had been attacked, but that the Enemy were beat off.[4]

It is not known if Amherst and Bouquet had knowledge of Trent’s actions when they discussed the idea, or whether Trent had been given orders to carry out the plan or came up with it on his own. An outbreak of smallpox did occur among the area Indians at this time, but it is impossible to know if blankets from Fort Pitt were the cause. If so, it would be the only known case of deliberate biological warfare in North America.

In the autumn of 1764, the English military went on the offensive. Colonel Henry Bouquet, the commander of Fort Pitt, led a force of nearly 1,500 militiamen and regular soldiers from the fort into the heart of the Ohio Country in October. Bouquet’s force moved westward slowly. He had no intention of surprising the natives. He hoped to avoid battle altogether by convincing the Indians that they had no chance against the sizable number of British soldiers. Bouquet had every intention of destroying the native villages, especially those of the Delaware Indians and the Mingo Indians, in eastern Ohio unless they surrendered and agreed to all of the colonel’s demands.

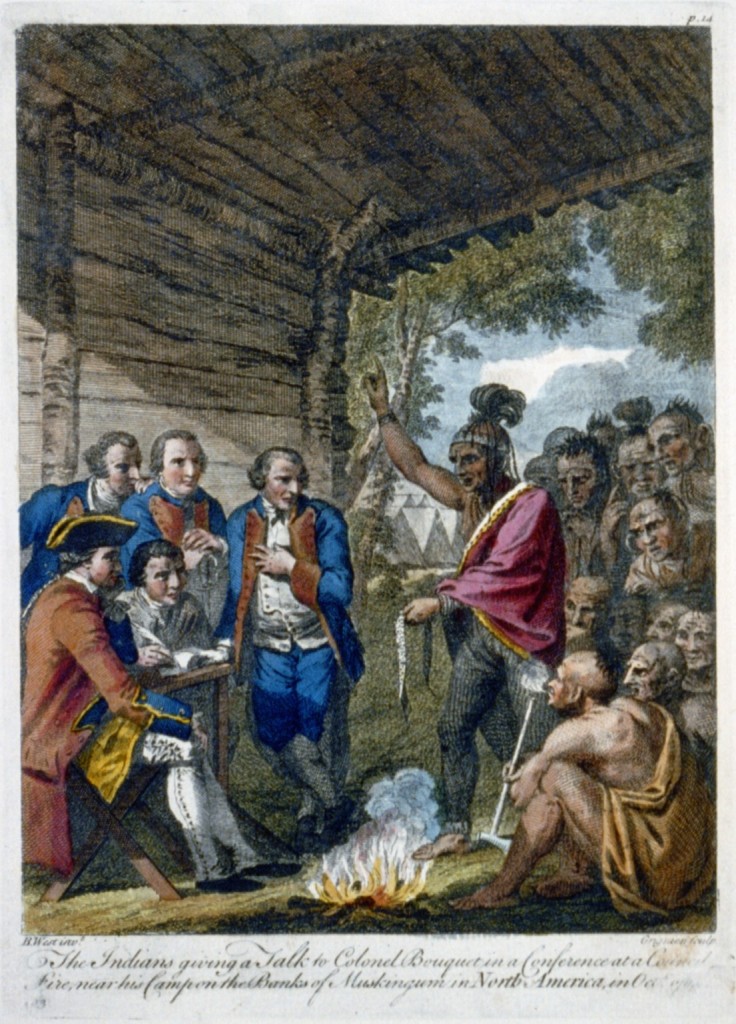

On October 13, Bouquet’s army reached the Tuscarawas River. Shortly thereafter the Shawnee Indians, the Seneca Indians, and the Delaware Indians informed Bouquet that they were ready for peace. They promised to return all English captives in their possession if the English spared their villages. Bouquet initially rejected the offer but then agreed to consider it. On October 20, he informed the tribes that English citizens demanded vengeance for the natives’ actions. He claimed that he would do all in his power to restrain them as long as the Indians returned all captives, including English and French men, women, and children, as well as any African Americans, within twelve days. They must also provide the freed prisoners with ample food, clothing, and horses to make the trek back to Fort Pitt. The natives agreed to all conditions, but fearing that they would renege on the agreement, Bouquet moved his army from the Tuscarawas River to the Muskingum River at modern-day Coshocton. This placed him in the heart of Indian territory and would allow him to quickly strike the natives’ villages if they refused to cooperate.

he return of the captives caused much bitterness among the tribesmen, because many of them had been forcibly adopted into Indian families as small children, and living among the Native Americans had been the only life they remembered. Some ‘white Indians’ such as Rhoda Boyd managed to escape back into the native villages; many others were never exchanged. Bouquet was responsible for the return more than 200 white captives to the settlements back east.

Over the next several weeks, the Native Americans brought in their captives. Eventually more than two hundred were returned to Bouquet. Several of the now freed prisoners welcomed the opportunity to return to their past lives. But many had become so accustomed to native practices that they did everything in their power to escape Bouquet’s grasp, including running away on the march back to Fort Pitt. Some even tried to return to the Ohio Country and Indian ways after returning to their white families. Bouquet promised not to destroy the Indians’ villages or seize any of their land. Bouquet’s army left for Fort Pitt on November 18.

Bouquet’s expedition showed how weak the Ohio Country natives were at this time. While they enjoyed some initial success in Pontiac’s Rebellion, the sheer number of English colonists in North America and their more advanced weapons meant that the Native Americans faced quite difficult odds.

In 1765, Bouquet was promoted to brigadier general and placed in command of all British forces in the southern colonies. He died in Pensacola, West Florida, on September 2, 1765, probably from yellow fever.

References and Suggested Reading

- Hurt, R. Douglas. The Ohio Frontier: Crucible of the Old Northwest, 1720-1830. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1996. – Available from Amazon.com

- Smith, William. Historical Account of Bouquet’s Expedition Against the Ohio Indians, in 1764: with preface by Francis Parkman and a translation of Dumas’ biographical sketch of General Bouquet. Cincinnati, OH: R. Clarke, 1868. – Available from Amazon.com