Flatboats and Ohio Rivier Migration

Ohio River Migration

The first flatboats, keelboats, steamboats, barges and towboats were built throughout the Pittsburgh region as it developed during critical periods in our nation’s history as the cradle of American inland river commerce. The history of transportation and development of viable waterways in the region dates back to 1739 when Captain Le Mercier, chief of Canadian engineers, cleared snags for navigation from what is currently known as French Creek for French troops advancing into the present day Pittsburgh region.

Captain Le Mercier became the first engineer to improve a stream for navigation in the Ohio River basin and set the course for what would eventually become one of the largest inland navigation areas in the country. Navigating the Ohio River during even the best seasons, summer and fall, was demanding and hazardous. Preparation throughout the year was critical and led to increased navigation success and profit.

George Crogan, an early explorer of the Ohio country, was permitted to negotiate with the Indians. The Illinois country was considered the most profitable trade territory. Fort Pitt, which was positioned at the headwaters of the Ohio, was in a fine situation to prosper as a boat-building center.

Boat building was set up as early as 1765 at Pittsburgh. Materials were hauled in by way of Philadelphia in wagons and by packhorses, timber being excluded. The firm of Baynton, Wharton, and Morgan employed six hundred wagons for this excursion. The Treaty of Fort Stanwix, in 1768, opened up an entirely new era in river transportation. With the arrival of the new adventurers at Pittsburgh, a craft that would accommodate the pioneers and allow for the proper transportation down the Ohio was needed. Advertising for sale “boats of every dimension,” was the occasion at Elizabeth, Pennsylvania.

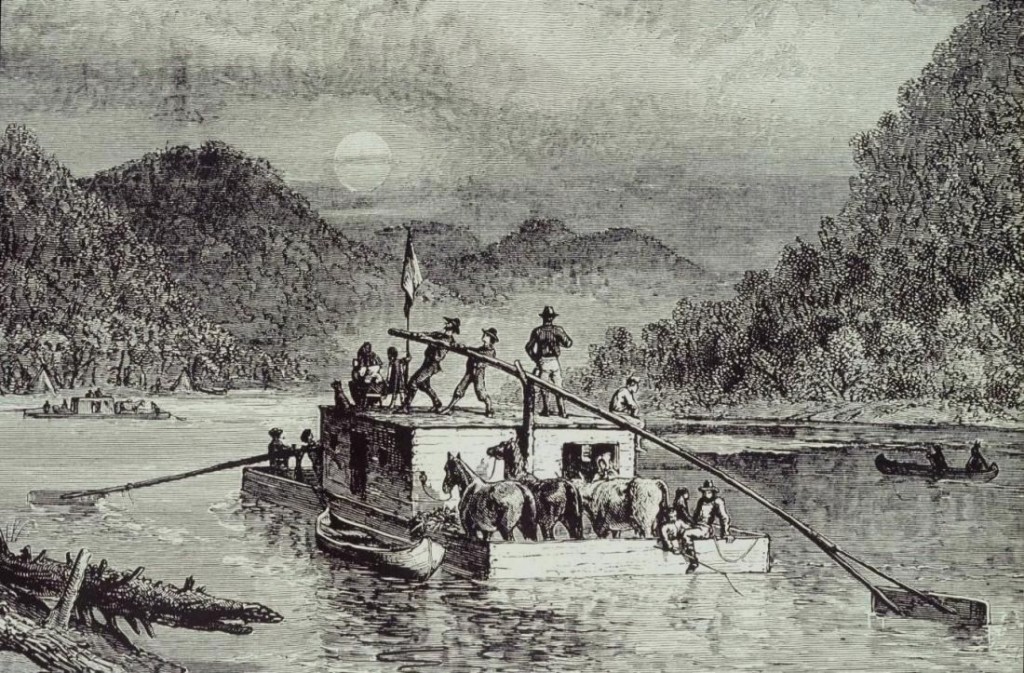

The evolution of the flatboat was at first canoes, pirogues and rafts but quickly began to transform into a more functional form of mass transportation in a variety of sizes. The first flatboats were only four to six feet in width, but were soon typically about fifty-five feet long by sixteen broad. Rectangular in shape and flat-bottomed, they were constructed of green oak plank, with no nails or iron. The heavy oak planks were fastened by wooden pins to still heavier frames of timber. The seams were originally caulked with pitch or tar, but as this was expensive, tow or some other pliant substance was later used. These rectangular shaped craft had generally boarded up sides from two to three feet high. The width and length had no standard size. The family generally set size preference. Even fully loaded, they drew only about three feet of water.

The smaller craft, used for shorter trips, were called Broadhorn or Kentucky Boats (circa 1788). They typically had no covering, but provided a shelter with a cooking area. Some versions had a rear shelter for horses and cattle and a forward cabin for the family. The larger long distance craft were called Mississippi Broadhorns, Keelboats, New Orleans Boats, Barges, or Arks and were typically covered throughout their entire length. Huck Finn refers to a flatboat as a ‘trading scow’ in Chapter 3 of Life on the Mississippi, by Mark Twain. These larger craft were useful in their own way, but the smaller flatboat had preference over the others because of its size and practicality.

The propelling of these boats was a task in itself. For navigation, all flatboats were propelled by “sweeps” which were mounted on the sides. The sweeps were used for directing the flatboat into the current, or for pulling into slack water when landing, rather than for propulsion. The great side sweeps, resembling horns from a distance, gave rise to the name Broadhorn. They also consisted of a rudder and a short oar in front known as the “gouger.” A “hawser” was a strong rope, which was mounted to a reel on board that, could be attached to a tree stump on shore, which in turn allowed the boat to be wound ashore. Because of its construction, descending the river was the only practical way of navigating. The flatboat was designated as “the boat that never came back.” It was broken up at the end of its journey and the lumber used for building houses, furniture, etc.

Boats were constructed in the fall, shippers loaded cargo in the winter and readied vessels for departure as soon as the ice broke in the spring. George Morgan, looking for ways to increase profit, built the first keelboat on the Ohio at Fort Pitt in 1768. The keelboat, called “la barge” in Louisiana, had an 18 inch runway along which the crew walked when poling the boat upriver. Keelboats ranged from 40 to 80 feet in length, 7 to 10 feet in width and drew about 2 feet of water when loaded. However, there were a few large “barges” that were up to 120 feet in length, 20 feet in width with a four foot draft.

The spring and summer of 1770 saw a great tide of river travelers. From 1768 through 1770, an aggregate count of river passengers was between four and five thousand settlers. The greatest interest for the settlers in the new territory was to begin a new life with more favorable living conditions. The lands on the upper Ohio were not best suited for these conditions, so their course was turned toward Kentucky.

The mass migration over the mountains and down the inland rivers after the American Revolution was the largest migration since the medieval crusades. The pioneers gained access to the Allegheny River at Olean, the Conemaugh River at Johnstown, the Youghiogheny River at West Newton, the Monongahela River at Brownsville or the Ohio River at Pittsburgh, Wellsburg or Wheeling.

The settler’s boat, navigated ever further down the eastern tributaries of the Mississippi in search of new land, was filled with household goods and farm stock. From the roof of the cabin that housed the family, cocks crowed and hens cackled, while stolid cattle peered over the parapet of logs built about the edge for protection against attacking Indians or freebooters. Sometimes several families would combine to build one ark. Often, when they chose a place to stop, they would re-use the ark’s lumber when building a cabin.

As these settlements multiplied, with increasing emigration to the west and southwest, river life became full of variety. In some years more than a thousand boats were counted passing Marietta. Several boats would lash together and make the voyage to New Orleans, sometimes navigating months in company. There would be songs and dances; the notes of the violin ~ an almost universal instrument among the flatboatmen ~ sounded across the waters by night to the lonely cabins on the shores, and the settlers would sometimes put off in their skiffs to meet the unknown voyagers, ask for the news from the east, and share in their revels.

Flatboats built by traders were able to carry as much as thirty or forty tons of cargo per trip. Down the Ohio came cloth, ammunition, tools, agricultural implements, and the ever-present whisky, which formed a principal staple of trade along the rivers. The proprietor would trade en route, blowing a horn to attract willing custom at any signs of settlement. Trade was mostly a matter of barter since currency was seldom seen in remote areas. Skins and agricultural products were all the purchasers had to trade, and the merchant starting from Pittsburg with a cargo of manufactured goods, would arrive at New Orleans, perhaps three months later, with a cabin filled with furs and a deck piled high with the products of the farm. Here he would sell his cargo, perhaps for shipment to Europe. The flatboat, unsuitable for upriver travel, would be sold for lumber, and the trader would begin his perilous journey back again to the head of navigation, wary of anyone who might seize his profit or his life.

The first parties to reach Columbia (now a part of Cincinnati) used the planks for construction of sheds and camps, this being the only form of habitable quarters erected at the close of the year 1788. By the close of February 1789, four cabins had been erected at Cincinnati, and ten or twelve camps or shanties had been built with the materials from the flatboats. A lady told of her first residence at Cincinnati that was a log cabin. The furniture consisted of one bedstead, one table, one chair and several wooden stools. The flooring was of boat plank, which was better than that of most of her neighbors, who had for floors logs split in two, and laid flat side uppermost.

General Josiah Harmar had noticed the large number of flatboats descending the Ohio and ordered the officer of the day to take an account of the number of boats that passed the garrison. From the tenth of October 1786, until the 12th of May 1787, 127 boats, 2,689 souls, 1,333 horses, 756 cattle and 102 wagons passed Muskingum bound for Limestone (Maysville, Ky.), and the Rapids (Louisville, Ky.). An average of 3000 flatboats descended the Ohio River every year between 1810 and 1820. In 1788, 323 boats passed down the Ohio, carrying 5,885 people, 2,714 horses, 937 cattle, 245 sheep, 24 hogs and 267 wagons. In contrast, in 2004 about 230 million tons of cargo transited the Ohio, with coal comprising about 50% of the freight, followed by petroleum, chemicals, farm products and manufactured goods.

At Limestone the boats became so numerous that they frequently were set adrift in order to make room for others. General Harmar noted that he had purchased at Limestone from 40 to 50 flatboats at the moderate price of from $1 to $2 each, to be used in the construction of Fort Washington at Cincinnati. In the winter of 1799, David Lowry loaded a flatboat at Dayton with grains, pelts and five hundred venison hams. The trip proceeded down the Great Miami in the spring. With the raising of the waters at this time of year, a two-month trip to New Orleans was accomplished. Lowry’s cargo was sold, along with his boat, and he returned by horseback. This was the first recorded trip from Dayton thru Franklin to New Orleans.

Keelboats greatly reduced transportation costs and, by the year 1800 were used for hauling the necessities of life upstream on the Allegheny, returning with agricultural staples shipped down by the pioneers. Although the flatboat preceded the steamboat, it was in regular use for many years after steamboats had become prevalent

As we’ll learn later at least one ancestor (John Adams), and likely others, traveled from Pennsylvania via the Ohio River to Kentucky in 1797. It is my belief that John started his voyage in either Pittsburg or Wheeling. We have record of land purchase in Bridgeport Kentucky in 1898. Bridgeport is located adjacent to Frankfort Kentucky on the Kentucky River. John would have traveled inland from some point on the Ohio River between Cincinnati and Louisville.

Note: There is a record of a semi-mechanical boat that was built at Fort Pitt in 1761 by William Ramsey. This apparatus consisted of two small boats joined together by a swivel in such a way as to make one. The boat was propelled by wheels attached to a treadle that was moved by the feet of the operator. As impractical as this boat was, it could turn in a shorter space than could smaller boats and that it could rise over falls with great safety.

On the following website:

http://www.eswp.com/PDF/

I learned the following: “The pioneers gained access to the Allegheny River at Olean, the Conemaugh River at Johnstown, the Youghiogheny River at West Newton, the Monongahela River at Brownsville or the Ohio River at Pittsburgh, Wellsburg or Wheeling.

In 1788, 323 boats passed down the Ohio, carrying 5,885 people, 2,714 horses, 937 cattle, 245 sheep, 24 hogs and 267 wagons.”

This is a U.S. Army Corps of Engineers-Pittsburgh article. Records must have been kept somwhere for them to have the #s anyway.